AT and the Geek Golden Age

The Assistive Technology (AT) Maker Movement has arrived! How might we use it?

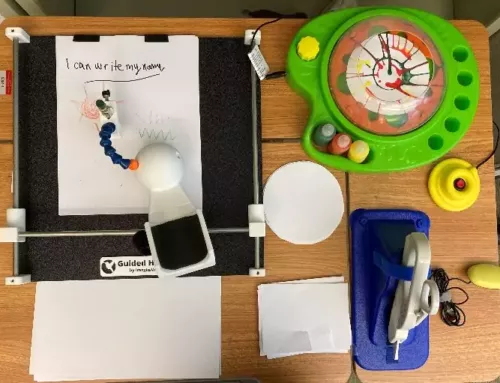

Photo courtesy of DIYability

There’s an assistive technology revolution underway that’s radically different from the rest. Already this decade we’ve seen a happy collision of mainstream consumer and disability tech that makes it hard to remember where we’ve been (speech-to-text once cost how much? Word prediction was AT only?) This time, however, the revolution is not about commercial products with AT potential (iPad!) or AT marketed to a mass audience (Amazon Echo!) In fact, this revolution has little to do with industry; it’s about geeks looking for projects that matter and people with disabilities empowering their inner geek.

For assistive technology users, family members and professionals, the maker movement is warmly familiar. It’s the ingenuity that has continued uninterrupted over several decades as we make solutions for ourselves and the people we love, know or assist (Puerto Rico’s LD3! New Hampshire’s Therese Willkomm!) The difference this decade is an emerging AT engagement by the rapidly expanding broader maker culture, and the high-tech solutions now within a hobbyist’s reach. These conditions, some believe, offer potential to disrupt the AT industry. Or at the very least, forever change our AT expectations.

“We’ve always designed assistive technology,” Mary Jo Wagner OT/R, ATP, mused on a recent tour of the Massachusetts Department of Developmental Services’ Kelley AT Center. “There weren’t products for our students. And custom-made is still better.”

Makerspaces are now common in communities around the US and the world. Equipped with sophisticated new desktop tools (3D printers, laser cutters, design software); hackers, engineers, and do-it-yourselfers are gathering, virtually and in-person, to share projects and know-how. The movement is grassroots and anti-establishment, fueled and funded by individual passions and often a desire to make a difference for people and communities. Yet it’s also formally embraced by industry, government and the nonprofit sector. There are makerspaces sponsored by the tech industry, private foundations, or created as for-profit workshops (learn the difference between a FabLab, TechShop and Hackerspace). In 2014 the Obama Administration launched an annual White House Maker Faire and National Week of Making.

Remarkably, this movement of utter coolness (think McGyver, think Jobs and Wozniak in their garage) is elevating not only the geek but also the whole sphere of disability itself. Makers, by their nature, enjoy functional and everyday challenges (consider the term “life hack”); they may also have a native respect for human ingenuity … which is, after all, at the heart of living with a disability.

Whatever the reason, makers are helping push disability into the mainstream. Social media is flooded with videos featuring adapted toy cars, 3D printed prosthetics, a million and one uses for paper clips. These AT solutions go viral because they are entertaining and within reach, a virtual celebration of what we can all now do as users, builders or both.

But if making is elevating disability, disability is also elevating the mission and purpose of making. Stephanie Santoso and Kate Gage, former Obama Administration Senior Advisors on Making, are now turning their efforts to connecting makers to global social missions and community-based projects. Their recent Medium article, “Makers for Global Good,” highlights several such efforts including 3D printed fetoscopes and BioSand water filters. Yet what project serves as their article’s lead? A motorized bookshelf designed by an 8-year-old and the global AT-maker group TOM.

Adafruit, an open-source maker electronics company, has even plugged AT making on their weekly YouTube show (Ask an Engineer). “When we started doing this Adafruit stuff,” Phil Torrone says, “we didn’t set out to do assistive technology. But, boy, it sure is working out.” Torrone advises his audience, “There’ll be people that you can potentially change their life. That’s a big deal. Not every hobby has that.”

For State AT Programs, this may be an exciting and game-changing moment. People not ordinarily engaged with disability concerns are taking an interest in our community. People with disabilities are taking their place at the center of the design process as well as using new tools, software and partners to engineer their own solutions (DIYability!) AT making is no longer created only in isolation, driven solely by necessity. It’s also improving existing solutions, bridging worlds and expanding access.

Mike Marotta, Director of the State AT Program in NJ (the Richard West Assistive Technology Advocacy Center at DRNJ), sees enormous potential for the AT maker movement and a positive role State AT Programs can play. “Makers are the perfect conduit for getting solutions to people with disabilities who have no funding or are waiting for services,” he says.

Marotta recently helped host an #ATChat on Twitter with Bill Binko, founder of ATMakers.org and the symbol system LessonPix. The ATMaker mission is to connect makers with authentic AT projects, and Marotta has invited him to keynote NJ’s next assistive technology conference. “It’s not just about getting devices people need,” Marotta says. “The maker movement is a chance to share an understanding with a whole new group of individuals who may not know anything about disability or assistive technology.”

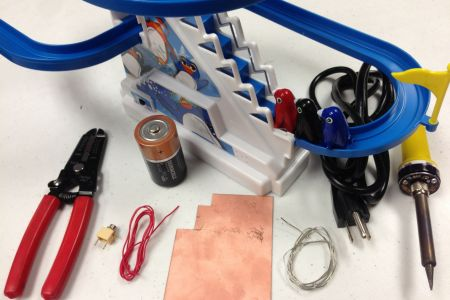

Binko is building these bridges and his assistance extends to State AT Programs. Based in Florida, he is currently teaming with FAAST and connecting authentic AT needs with Factur, a makerspace community. Together they are planning a makeathon to create switch-adapted toys for children within the FAAST network. “FAAST used to hold a 5K run to raise funds for buying switch-activated toys,” he explained in a recent interview. “They bought something like 30 toys with those proceeds. This year, we have the potential to create hundreds by having makers adapt store-bought toys.” He plans on providing the projects and training, in consultation with another national AT maker effort, Santa’s Little Hackers. He’s also going after corporate sponsorship (“Raytheon, Siemens and Honeywell are big supporters of the maker movement,” he says).

Marotta and Binko are ideal evangelizers for the AT maker movement; both are engineers by training; both have long histories working with the disability community. Binko has the added perspective of someone who has developed and marketed AT products and sees with an AT vendor lens. He founded ATMakers.org out of frustration with the AT industry which he sees as sluggish to innovate and trapped by Medicaid and the DME funding process. A tour through the ATMakers public Facebook group, however, shows he also just loves to make stuff.

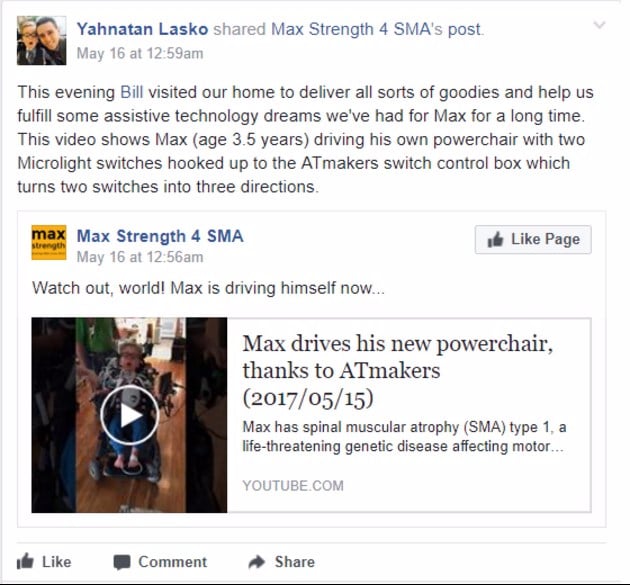

Binko’s work with Max Lasko and his father Yahnatan has included creating a custom-switch controller for Max’s power chair that bluetooth-connects with a telepresence robot.

Binko’s effort is also directed at middle and high school STEM programs and robotics clubs. “Geeks want real challenges and these clubs have the skills and the equipment,” he observes. He’s been working with the Loudoun County Public Schools AT team in Virginia where middle schoolers can now join an AT Makers Club (check out Mark Nichols and Judith Schoonover’s ATIA 2017 slides on this effort). “AT projects offer an opportunity to use that 3D printer in a way that matters,” he says.

One of Binko’s favorite initiatives is to 3D print adapters to commercial camera mounts. The adapters connect AT switches to a world of low-cost mounts readily available on Amazon. The instructions are available to anyone at ATMakers.org (Easy AT Switch Positioning w/Free 3D Printed Camera Mounts). “They’re a great way to start with a school club,” he says.

For State AT Programs, engaging the maker movement for unique AT solutions could become a strategy that fills service gaps similar to the way reuse functions as a work-around to DME acquisition challenges. It’s yet another way to get AT or as a bridge to funded equipment. But it’s clear that Binko and Marotta also see it as much more than that. “It’s not all about 3D printing,” Marotta muses. “It’s about getting in a mindset; it’s about problem-solving and creativity.”

It’s also how AT making creates relationships. Indeed, developing solutions involves close communication and collaboration among makers and users. It promote greater understanding with concrete benefits. “Don’t just approach a STEM club hoping they’ll be your tech support–ask them to help design a solution,” Binko says. “But eventually, oh yes, they will become fantastic tech support as well!”

AT making has always been with us, and now the maker movement is exploding its potential. Marotta says, “I used to tell people, ‘You’re not at AT person until you’ve made a key guard for a computer, and drilled the holes and cut up your hands.’ It was like a right of passage! Now technology has come of age and there’s this opportunity to make the devices we really wanted to make 25 years ago!”

Ready to get started? Here’s some advice for State AT Programs from Bill Binko:

- Reach out to STEM clubs in high schools, colleges and even middle schools. “They have the greatest concentration of resources; they have access to all of the tools and skills, both the students and the mentors and they are looking for service projects and they don’t have a clue that you exist.”

- Reach out to FIRST Robotics Clubs, they have skills! But be ready to adapt to their robotics competition schedule.

- Reach out to Makerspaces. These operate like the YMCA; people join to access a workshop equipped with laser cutters, 3D printers and other maker tools and materials.

- Reach out to local tech companies (sometimes they sponsor community maker spaces). Do they do a day of service? Are they hackers and makers? Become their day of service!

- Begin with an “easy win”: ask them to adapt a toy, mount a switch, 3D print something you need. Bring them a known “good project” for assured mutual satisfaction.

- Consider configuring home automation for a community member using Amazon Echo or Google Home. “This is empowers both the students and the community member who can now adjust their heat or turn off the lights.”

- Begin knowing what you need and how they might help, but also have a wish list of problems without solutions. “Geeks want problems to solve on their own.”

- Give them the opportunity to learn about disability and meet people who use AT. These are profound experiences for students who have had no exposure to people who use AT and who need their help. “They are never taught to ‘Presume Competence’ or how to talk to an SGD user–this is great for them!”

- Be prepared for questions. Be prepared for: “why are the adults not solving these problems for this person already?”

- Be ready to reward the group in the way that they want. For school-based clubs this is often a picture of their solution for their website. If possible, be ready with that photo-release form from the family they are helping!

- If you don’t know how to start, ask Bill, Mike and the other folks at ATMakers.org to manage an introduction; they’ve done this before!

Monthly Blog Digest

Search the blog

State AT Program Blogs

California

Florida

Indiana

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Montana

North Carolina

North Dakota

Utah

State AT Program Blogs

The AT3 Center, the Association of AT Act Programs (ATAP), and the Administration on Community Living (ACL) make no endorsement, representation, or warranty expressed or implied for any product, device, or information set forth in this blog. The AT3 Center, ATAP, and ACL have not examined, reviewed, or tested any product or device hereto referred.